At last… A month has passed, then two and now almost three, I’m so torn between the great memories of finishing this beast and the delay in recollecting my thoughts and journey related to this major accomplishment of my 2023 season. Let me try to get at least one part of it out in the same year. All this time I had kept 2 or so dozens of tabs opened in Chrome to get prepare for the big endeavor and, yesterday, I got a major crash and that corrupted my browser. I ended up losing 420 tabs out of the 560 I has still opened after recently closing 200. I know, that’s erring on the ultra multi-tasking side…

After taking a week off for Spartathlon, not to mention months of preparation, I had a lot to catch up and focus on, including finding another role in IBM in a challenging and stressful setup. Plus the family, friends, more racing and training, a few trips, several major milestones in my volunteering gigs (USATF and AFAM) and key home maintenance projects.

Yet, as a pro procrastinator multi-tasker, I never stopped thinking of this project. First, I thought I’d wait for the official race pictures, and that took 3 weeks in October. Then I was waiting to receive David Crokett’s book in which he covers the history of Sparathlon. Then, the intimidation of the sheer size of recounting such an experience. Then, as mentioned above, all the rest…

As the saying goes, and not just about Big Blue, the best way to eat an elephant is bit by bit, one bite at the time. Before the race, I came up with the idea of splitting my race report into 4 parts. And since I studied Greek for 2 years in middle school and loved it so much thanks to an amazing teacher, Mr. Goudet, who also taught us about Greek and Roman history and mythology, picking 4 Greek words as themes (I can still read Greek, but that doesn't help understanding modern Greek though):

1. The history of the race, or γένεση (genesis);

2. The preparation phase, or προπαρασκευή;

3. The race itself, or αγώνας (which doesn’t mean agony but race!);

4. The post-race phase, or επίλογος (epilogue).

Interestingly or oddly enough, the timespans covered by each part are really different: a few centuries for part 1, almost 9 months for the second, less than 2 days for the race itself, and weeks or now months for part 4.

A few centuries, that’s going to take time, right? I have to confess I’m really not great at history, one of the many topics my dad was mastering with his encyclopedic culture, but I really love it, that so much experience is made available for us to leverage and learn from. As a matter of fact, that is one thing which exasperates or depresses me these days, to see how stupid our world remains by still fighting wars, like we don’t know how bad they are and how much they hurt short and long term. Especially in this digital age in which we have access to so much information in real time, or artificial intelligence, really? But I digress...

The Pheidippides and Marathon myths

Well, speaking of conflicts, that’s of course one major historical connection to Sparathlon, with the battle of Marathon. That battle is certainly not a myth: in 490 before Christ, the Persians (from today’s Iran) were sailing toward the coast of Greece to invade the country as they had done through the middle east already. Despite their overwhelming numbers, the Persians got defeated by the Greeks, or more precisely the Athenanians, and that battle became a pivotal moment, leading to 200 bright and dominating years for the Greek civilization in particular.

Now, let’s talk about running. First, the historical and geographical facts. Yes, there are about 40 kilometers separating Marathon and Athens. Yes, Athens and Sparta were the dominating cities of Greece. Yes, Athenians and Spartans weren’t really friends, they actually had their own army. Yet, it seems very legit for the Athenians to send a messenger to Sparta to ask for help, given the frightening danger of the Persian invasion and the size of their army and fleet. And, yes, the modern marathon distance is 42.195 km after the addition of a 2-kilometer detour at the London Olympics so the King of England could see the race from his castle.

But what about the story about Pheidippides racing to Athens after the Marathon victory and dying after announcing the joyful news? Which is of course what everybody knows about the origin of our mythical marathon race format, right? (By Luc-Olivier Merson - [1], Public Domain.)

While the Marathon messenger seems to have existed, and even died after the rush, it was most likely NOT Pheidippides. Although Pheidippides was indeed a messenger who more likely was sent to Sparta a few days before the battle, to ask the Spartans for help. The Spartans argued that they could come when their ongoing religious festival was over, and also waiting for the full moon. With that, even if you might be disappointed by learning Pheidippides wasn’t the one running from Marathon, he still covered the distance of 6 marathons, reportedly reaching Sparta before the dawn of the second day, then returning by foot and over the famous Mount Parthenion, where Pheidippides was instructed by the god Pan to let the Athenians know he would help them if they were to worship him again. Myths and legends are sure to make and keep Sparathlon mythical!

I have to say that, after 25 years of intense and competitive running, I find surprising to have to enter the Sparathlon in order to figure all this out. Even the Wikipedia page is still ambiguous about all these myths, despite what seems to be enough historical evidence available today…

Fast forward 2,500 years, the demystification experiment

There is hopefully much more clarity in the roots of today’s Spartathlon. In addition to what you can find on the web, ultra historian Davy Crockett recently published the book “Classic Ultramarathon Beginnings” in which he covers Sparathlon over 39 pages in chapter 9. A great read full of details about John Foden in particular (some details also available on Davy's remarkable Ultrarunning History website).

In line with the weaving of history by conflicts, John was in the Royal Air Force when he formed the dream to check if it was indeed possible to run from Athens to Sparta in 36 hours or less. He was joined by 4 other British military men and a crew of 6 composed by an eclectic mix of British and local teachers and students. They started their experimental journey on October 8, 1982. While Foden missed the 36-hour goal, he still managed to finish in 37:37, despite being the oldest at 56. John McCarthy finished in 39 hours. John Scholtens actually claimed a 34:30 finish but, later, Foden stated that Scholtens must have had taken a 10-mile shortcut, off the planned course. Still, they were delighted to have demonstrated the feasibility of Pheidippides’ legendary run and thus was born a new mythical race!

41 years later

Thanks to the entrepreneurship spirit of local Michael Callaghan, the first official race was held a year later on September 30, 1983. It had 45 starters from 12 countries, 44 men and 1 woman. 16 finished and the winner was no other than the ultra famous Yiannis Kouros, already setting the bar super high at 21:53! He will lower that already mind blowing mark at 20:25 (make a note for this year’s edition). He would end up winning the race 2more times in 1986 (21:57) and 1990 (20:29). The ultra king, or god…

Our own Scott Jurek would end up winning 3 consecutive times in 2006, 2007 and 2008, with times ranging between 22:20 and 23:12.

Last year, the 40th anniversary run had 182 finishers.

What else to know

The race format

Of course, poor Pheidippides didn’t have a paved road to follow between Athens and Sparta! Nor aid stations, nor running shoes, nor energy gels, chews, sun glasses, anti-chaffing lube, crew, all the support we now get.

Today’s course is 153 miles or 246 kilometers, all on pavement except for 3 miles of rocky trails over Mount Parthenion. If asphalt looks better than trail from a running performance standpoint, most roads are open to traffic and half of these roads are actually busy highways. That is one part of the experience which I was not looking forward to, although I did many miles of training on such roads in Europe and the US, to help prepare.

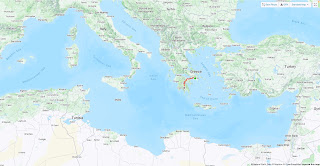

Here is how the course looks on a map of Greece:

The elevation isn't terrible, my Coros watch measured a gain of 9,800 and loss of 9,500 feet, with Mount Parthenion culmunating at 4,000 feet (1,215 meters).

Beyond the intimidating distance, one which I had never covered in one shot with my longest being 133 miles at the 2014 24-hour Nationals, there is also the pressure of a 36-hour cut-off. And to make the matter worst, not just one cut-off but 75 of them as you can get pulled at each of the 75 checkpoints along the way. And to make the matter even worst, the pace isn’t even linear, not just to take into account the course profile but also to factor in the fact that you will likely slow down. Although it is highly NOT recommended, you still have to start at a faster pace to make these cut-offs early on. While the overall pace corresponding to the whole 36 hours don't seem outrageous at 14:08 min/mile, the first part should be run at close to 10 min/mile, you have to keep moving!

How to get in

Between the myth, the international format, and the 40-year history, you’d think the entire planet would want to enter that race. In an interesting dilemma, the organization committee wants to keep the event both open to as many as possible, internationally, but without making a big fuzz out of it.

First, the qualification criteria which I include below for your perusal. Note the lack of generosity for women for whom the minima are really close to men’s. I used to easily meet criteria a to e a few years ago, it was time to put my name in the hat with a couple of “b” qualifiers.

INTERNATIONAL RACESa) Cover a 120 km (men) or 110 km distance (women) within 12-hours.b) Finish a 100-mile race in 21:00 hours (men) or 22:00 hours (women).c) Finish Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run, within 24:00 hours (men) or 25:00 hours (women).d) Cover at least 180 km (men) or 170 km (women) in a 24-hour race.e) Finish a non-stop 200-220 km race within 29:00 hours (men) or 30:00 hours (women).f) Finish UltraBalaton (221 km) in 31:00 hours (men) or 32:00 hours (women)g) Finish a longer than 220 km non-stop race within 36:00 hours (men) or 37:00 hours (women).h) Finish Badwater race within 39:00 hours (men) or 40:00 hours (women).i) Finish Grand Union Canal Race within 34:00 hours (men) or 35:00 hours (women).j) Finish Sakura Michi 250-km race in 36:00 hoursk) Finish Yamaguchi 100 Hagi-O-Kan Maranic 250-km race within 42:00 hours (men) or 43:00 hours (women).l) Cover a distance of at least 280 km (men) or 260 km (women) in a 48-hour race.RACES IN GREECEa) Finish Spartathlon race within 36:00 hours.<And a few other local races>

Second, the field remains limited to 390, not far from the Western States Endurance Run quota of 369. But it’s actually more complex than just a single number: to maximize international representation, the organizers limit to 25 the number of runners from each country, just keeping 50 aside for the Greeks. They also reserve the right to invite a dozen or so elites.

Besides, runners meeting the pre-requisite marks by 25% or more are auto qualified, meaning they don’t have to go through the lottery. Depending on the size of the country, and the popularity of Spartathlon within that country, the odds vary a lot. For instance, there was only one entrant representing the 1.4 billion Indians! Conversely, and thanks especially to Bob Hearn’s advertising of the event in our local circles, we had quite a few Americans on the wait list this year. Including Bob himself, victim of his own marketing efforts to advertise for Spartahlon. Bob was trying to enter for the 6th time, for a 5th finish.

But... why did I get in?

That's a question I got quite frequently through 2023. Primarily, I felt that, one year before turning 60, it was about time I give it a try. I had thought of entering before but it felt way too intimidating, between the international reputation, the distance and the international logistic. Beyond the athletic challenge and must-do nature, I was also attracted by the mythological and historical connections. As I mentioned, I loved that subject in middle school thanks to the communicative passion of our teacher.

I felt important to give you in that initial part some background so you can put some perspective on the unique nature of the event. Which Davy Crockett labels himself as: "one of the most prestigious ultramarathon in the world." In the next part, I'll cover the 9 months leading to the race. A kind of pregnancy...

1 comment:

Looking forward to the next installment Jean!

Post a Comment